With around 1200 species recorded worldwide, approximately one quarter of all known mammals are bats – only the rodents are more speciose. Bats occur almost everywhere on land, and are present on all continents with the exception of Antarctica.

Bats belong to the order Chiroptera, meaning ‘hand-wing’, which is split into the sub-orders Megachiroptera - the Old World fruit bats - and Microchiroptera. All seventeen resident British species are Microchiropterans. Two - the Greater horseshoe Rhinolophus ferrumequinum and the Lesser horseshoe R. hipposideros - belong to the family Rhinolophidae, and the remainder belong to Vespertilionidae; which is the largest mammalian family after Muridae (the Old World rats and mice). Yet, despite their evolutionary success, an estimated 15 percent of all bat species worldwide are now threatened with extinction by habitat loss, persecution and disease; and in the UK, all native species require protection from both national and international legislation.

Northern extremes

Being a small insectivorous mammal, living in a temperate climate has its drawbacks. Firstly, food supply is seasonal; secondly, being so small, much body heat is lost to the surrounding cooler air. Our bats overcome this by entering periods of torpor and hibernation in order to conserve energy. However, this strategy has its limits and there still exists a gradual loss in species diversity with increasing latitude. For example, in Devon, in the south-west of the country, sixteen species have been recorded (1); whilst up here in Durham, eleven species have been recorded – one of which remains unverified, and only eight of which are known to breed (2). Nevertheless, this figure may come as a surprise to many, especially those who are not even aware that bats are around us – sometimes quite literally!

Detecting bats

Bats are notoriously difficult to follow and to study, owing to their diminutive stature, nocturnal lifestyle and accomplished flying skills. Even here in the UK, with our rich history in the natural sciences, bats remain an enigma, and there is still very much to learn of their behaviour and ecology. However, there is an element of their anatomy and physiology that, in recent years, we have been able to exploit in order to begin scratching at the surface – this is the process of echolocation.

All Microchiropteran bats possess the ability to orientate by echolocation; which they achieve by emitting sounds through their mouths or noses and detecting the returning echo from solid objects. The average amplitude, duration and frequency of calls differ between species; so, in theory, we should be able to unmask a bat’s identity by measuring these parameters – if only it were always that simple! There is much overlap in the call parameters of closely-related species, and to add to the confusion, an individual will vary its call according to its foraging strategy and the habitat it is using. As a result, equipment and software has become increasingly sophisticated (and expensive) in order to assist a growing army of demanding bat hunters. However, detecting and identifying bats needn’t break the bank, and much can be achieved using a (relatively) inexpensive frequency division bat detector, an MP3 recorder and freely-available sound analysis software.

The bat year begins with the end of hibernation, usually in March or April. On at least one evening in each month since March, I have taken a stroll around the perimeter of Great High Wood, stopping briefly at strategic points along the way, such as ponds, pasture and edge habitat. I listen to my detector over headphones and make notes of when and where I hear a bat. In the background, my MP3 recorder dutifully records everything that the detector picks up. Once indoors, the sound file can be downloaded to a computer and analysed using the sound analysis software. This is invaluable for verifying identifications made in the field, as well as for making sense of unidentified calls, and sometimes, for finding calls that were missed completely!

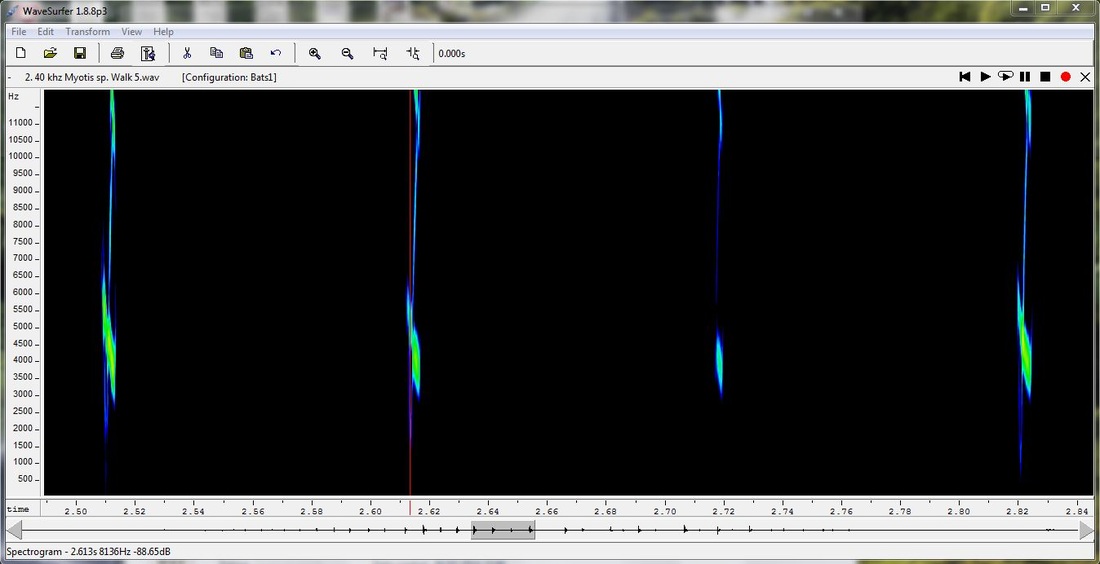

It is difficult to put an exact number on the total species I have recorded around campus – it could be as much as nine or as few as five. This is mainly because the echolocation calls of bats of the genus Myotis are very difficult to tease apart - even when viewed on a sonogram; and far more experienced ‘batters’ than I will often record them only as ‘Myotis sp.’. Below is a round-up of the species recorded, whether positively or potentially identified, along with both 'visual' and acoustic examples of their calls.

It is possible that I have recorded up to four Myotis species; but in reality, it is more likely to be two or three. The Whiskered Bat (Myotis mystacinus) and Natterer’s Bat (M. nattereri) are likely suspects, and, although strongly associated with water-bodies, Daubenton’s Bat (M. daubentonii) will also utilise the woodland. Brandt’s Bat (M. brandtii) is the fourth Myotis species recorded in County Durham, but is much rarer.

With a wingspan comparable to that of a blackbird (Turdus merula), the noctule is Britain’s largest bat. However, its body-size is far smaller, and even the largest of individuals weigh less than half that of the bird. The noctule is a fast and efficient flyer, utilising open spaces to hawk for its insect prey. It is the earliest species to take wing in the evening, and can be seen (or heard) even before the sun has met the horizon. I recorded this species in the pasture around Houghall Farm just to the south of Great High Wood.

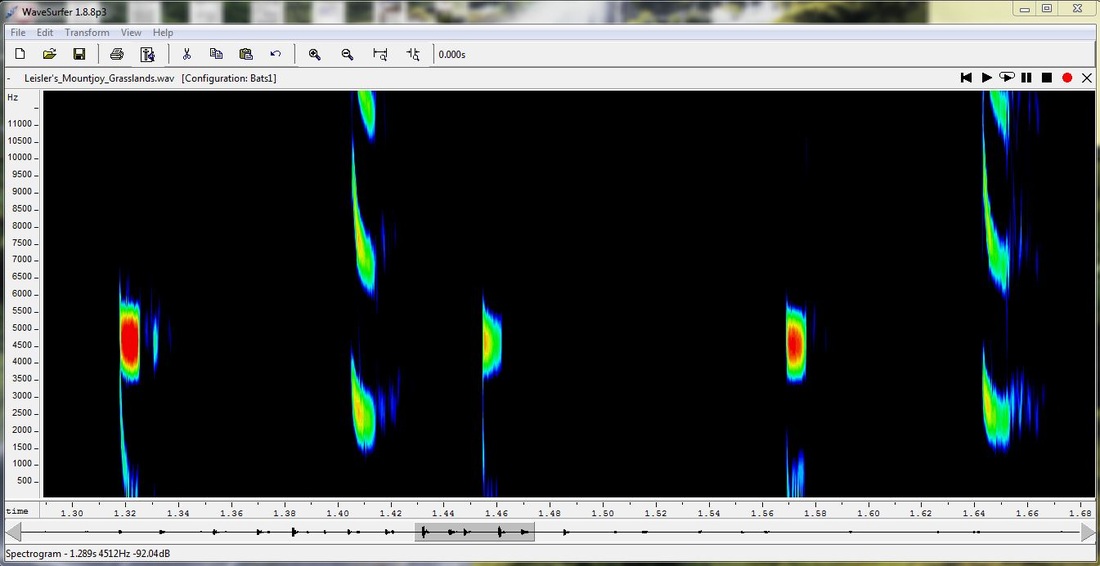

There is a second species in Britain that belongs to the genus Nyctalus – this is Leisler’s Bat (N. leisleri). A large Leisler’s individual is about the size of a small noctule. It emits the same ‘chip-chop’ echolocation call as the noctule, but, on average, it is a higher frequency. Back in mid-May, I made two separate recordings of calls with parameters that fit Leisler’s Bat very well – one in Houghall Farm pastures, and another in the grasslands around the Mountjoy Centre. However, since then, I have been reliably informed that this species is very scarce in County Durham, and that the calls were more likely to be those of Noctule. Nevertheless, I am going to remain ‘on the fence’ about this one, and record it simply as Nyctalus sp.

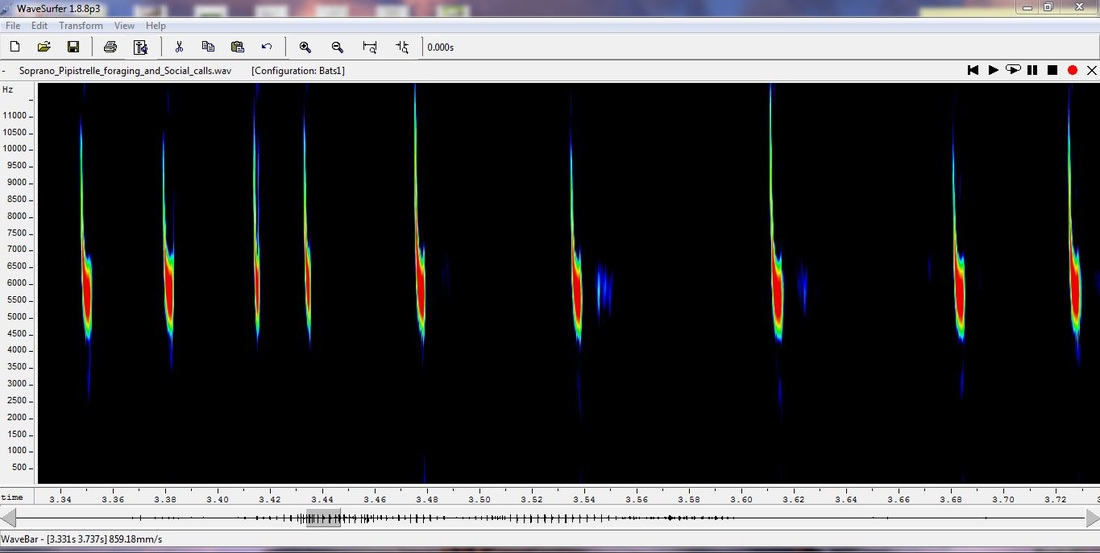

I have recorded two pipistrelle species in and around Great High Wood – the Common Pipistrelle (Pipistrellus pipistrellus) and the Soprano Pipistrelle (P. pygmaeus). Aside from being our two commonest and most widespread species, these are also our two smallest; and, astonishingly, some individuals may weigh less than a two pence coin – or roughly the same as a Goldcrest (Regulus regulus; for those whose currency is birds). The two species are very similar and were identified as separate as recently as the 1990s; but with a little practice, they can be readily identified in the field by their echolocation calls – the peak frequency of the Common Pipistrelle being around 47kHz, and the Soprano around 55kHz (although there is some overlap around 50kHz).

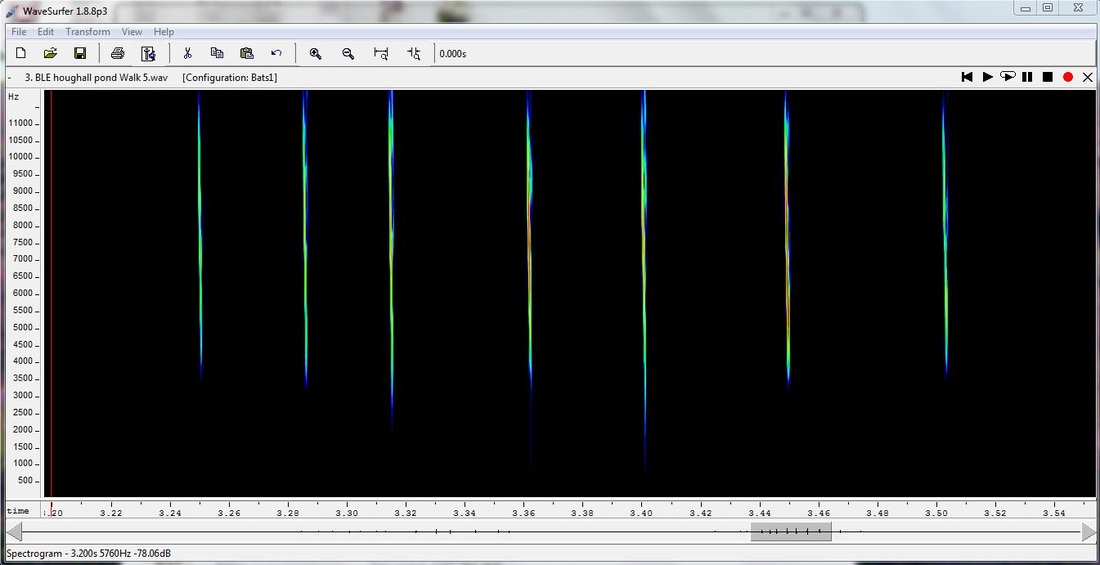

After the Common and Soprano Pipistrelles, the Brown Long-eared Bat is probably Britain’s next most abundant species. However, it has a very quiet echolocation call, often described as a 'light purring' or 'like the clicks of a Geiger counter', and a bat must be no more than a few metres away in order to be picked up by the detector. Consequently, despite its common status, I have recorded this species relatively infrequently.

The Brown Long-eared bat’s short, broad wings are suited to slow, manoeuvrable flight, and it sometimes hovers using its enormous ears to listen for its moving prey before picking it from the surface of vegetation. The species’ main prey is moths, with which it is locked in a coevolutionary ‘arms-race’. Many moths have evolved the ability to hear an approaching bat’s ultrasound, which allows them time to take evasive action. However, aside from having a very quiet echolocation call, the bat’s huge ears and relatively large eyes (compared to those of other bats) are adaptations to hunt using sight and sound; thus, avoiding detection.

I have recorded this species at the Mountjoy Pond, Houghall Pond and along the edge of Great High Wood itself. There is also a known roost within Hollingside House in Hollingside Lane - which they share with Common and Soprano Pipistrelles and an as yet unidentified Myotis species. I was privileged to witness some of these species emerge from the building when I joined Durham Bat Group for a dusk survey in July.

| By Stuart Brooker Stuart is a MscR student with CEG studying spatial relationships between biodiversity and ecosystem services in urban environments |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed