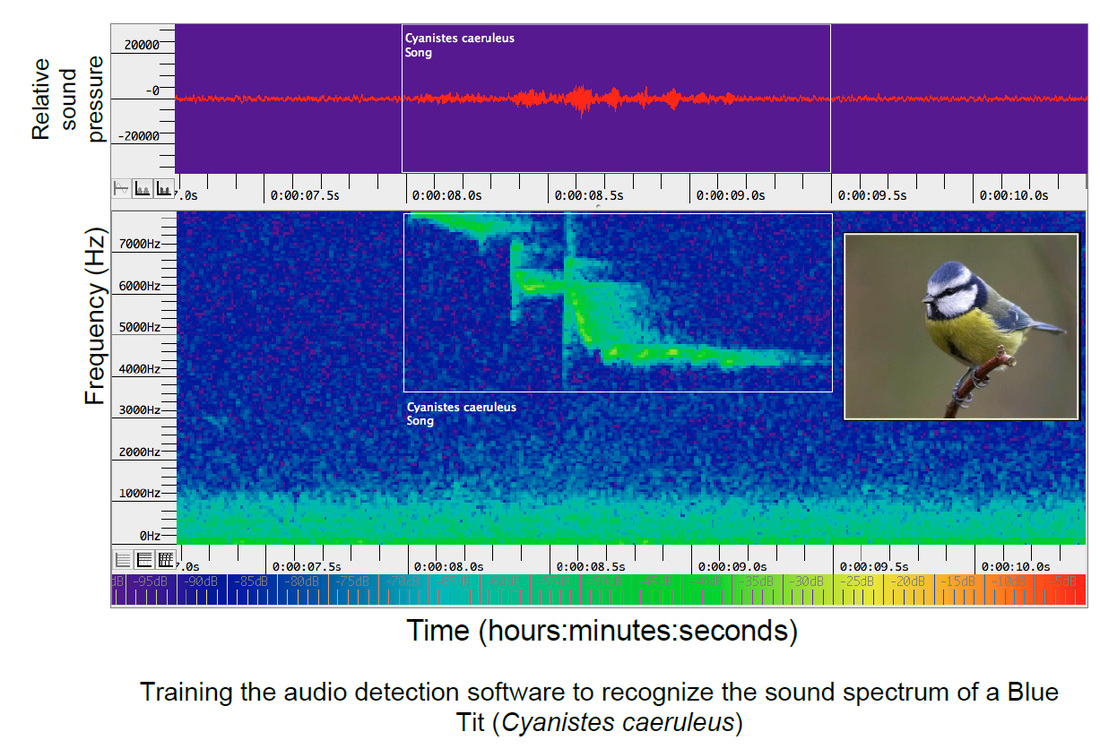

We will be using newly available acoustic recorders and automated song recognition software to monitor and characterise the dawn chorus as its spreads across the UK. We deployed 20 recorders across UK woodland in 2014 and have just redeployed them again to monitor the onset of this year’s dawn chorus, which is now becoming apparent as dawn gets earlier.

We’ll post updates on the project, which is working in collaboration with RSPB reserves across the country, during the course of the project.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed