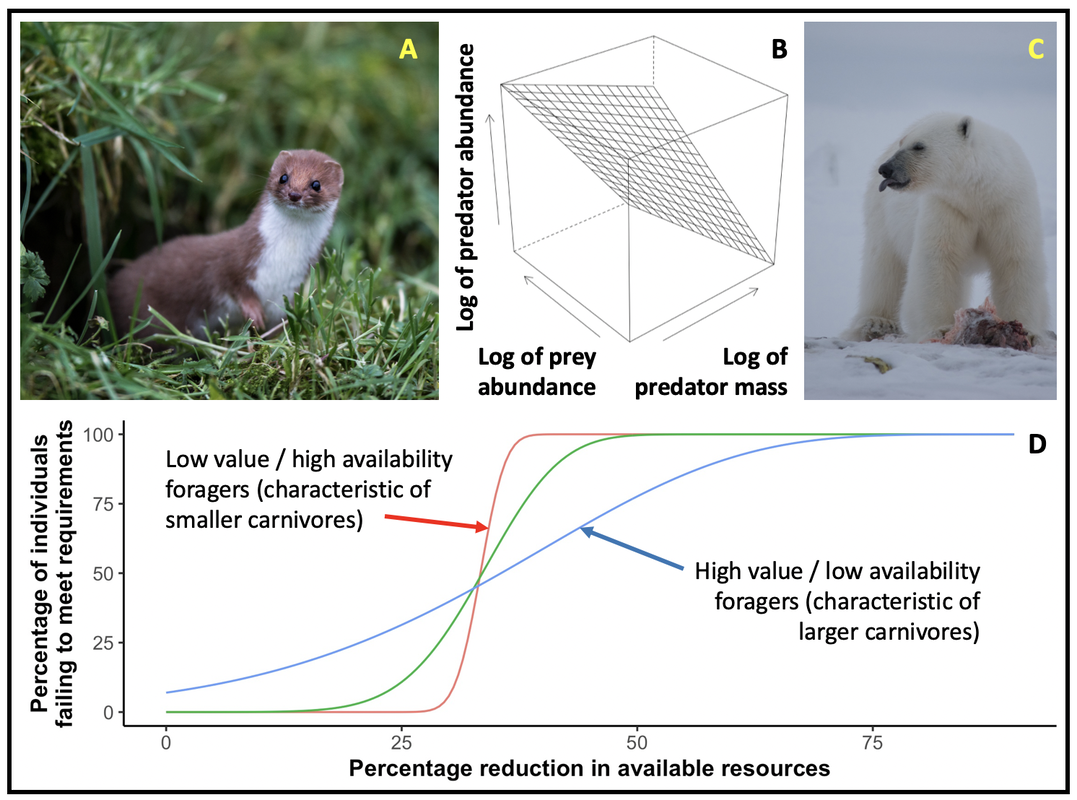

This finding vexed us because, although we could think of a variety of possible explanations, we couldn't find empirical or theoretical support for any of them. A new paper by Rory Wilson and colleagues presents a possible explanation. Specifically, for a variety of animals with different diets, they present empirical data on the time taken to find and ingest food items. Perhaps unsurprisingly, they find that foragers focusing on low value but highly abundant food (such as grazers eating grass), the time taken to find and ingest food is low and, as a result, the variation in that time between different individuals is also low. By contrast, when foragers focus on high value but low availability foods (like large carnivores preying on large herbivores), the time taken to find and ingest food can be very high; moreover, the variance in time taken by different individuals - simply as a consequence of luck in finding food - can be huge. As Wilson & co. show, this can have very important implications for population dynamics. This is because, as long as food is suitably abundant, low value / high availability foragers will all acquire enough energy to survive and reproduce (and there will be limited variation between individuals in their capacity to do so). However, for high value / low availability foragers, there will be high variation between individuals; simply by chance, many individuals may fail to acquire sufficient energy to survive and reproduce.

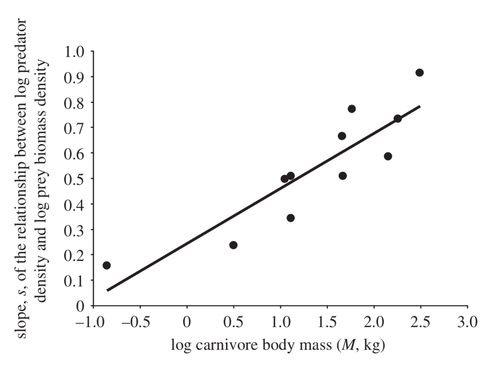

In an overview of the importance of Wilson et al.'s new paper, now published in the journal Current Biology, Phil argues that it could influence our thinking about a wide variety of phenomena in ecology and behaviour. These range from the role of diet and luck in determining the evolution of lactation and capital breeding, to food-sharing and alloparenting (with profound implications for the origins of sociality). Importantly, as a result of the link between diet and body size, the modulating effect of body size on luck and population dynamics might thus be expected to explain the strong influence of carnivore body size on the strength of the relationship between food availability and carnivore abundance (see Figure 2).

With further information on the search times of a wider range of species, it might become possible to establish the body-mass scaling of these phenomena. Integrating them with other allometric relations, such as time to starvation, will enable broader, macroecological predictions regarding their implications. It might also be possible to identify sources of autocorrelation in the measured search times of specific individuals, and to identify how much of inter-individual variation is due to luck and how much is due to variation in competence. There is a need to consider the role of handling time which, itself, will induce negative correlations between luck and time available for foraging. These considerations all highlight that further consideration of the inter-related roles of diet and luck could be an active and productive field, which could yield important further insights for a range of disciplines within population and evolutionary ecology.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed