Wicked Complex Conservation Conflict

Conservation conflict in which people disagree about how to manage biodiversity and parties are perceived to assert their point of view to the detriment of others is an example of a Wicked Problem. Actually, to be honest there are loads of issues in conservation science that can be dropped into the complex, bubbling bucket of wicked problems. Are you dealing with lots of uncertainty? Finding the boundaries of the problem difficult to define? Lacking clear solutions that don’t cause problems elsewhere? Experiencing multiple feedback loops which interact with non-linear dynamics? Yep, you’ve got yourself a wicked problem there, pal.

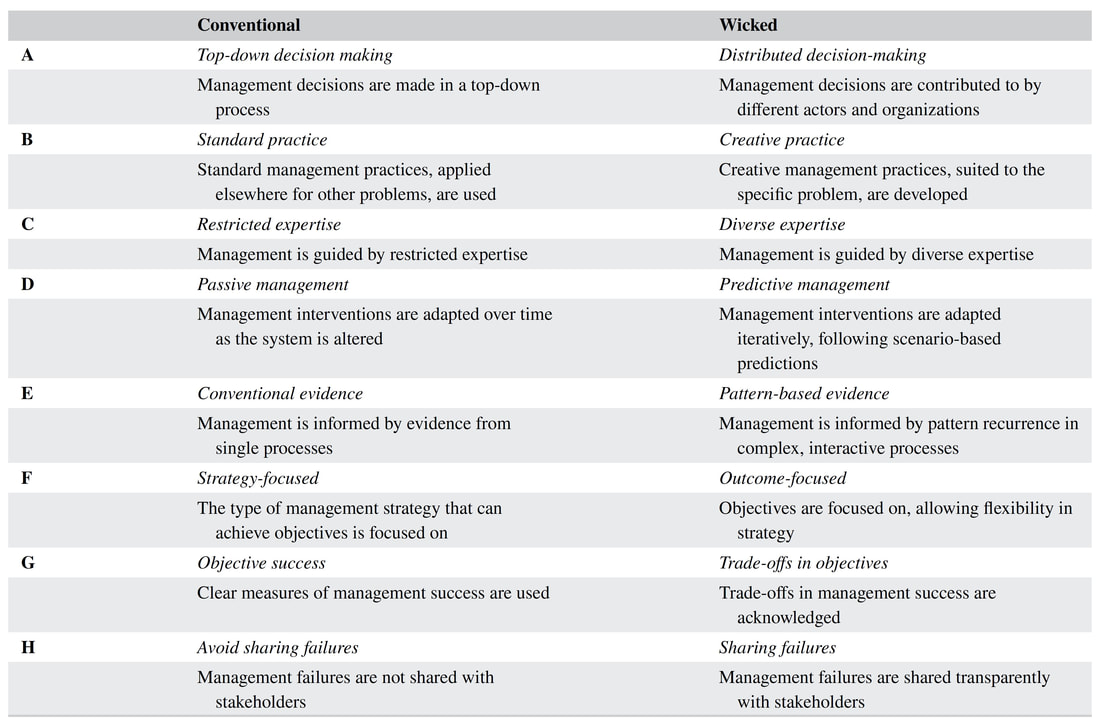

In 2014, Game et al., described conservation challenges as operating under wicked problem conditions, providing a starter list as to where the common, conventional, “tame” approaches to conservation science were falling short (see also DeFries & Nagendra, 2017). Game et al., also helpfully, provided some wicked alternatives, pointing researchers towards the complexity-type thinking required.

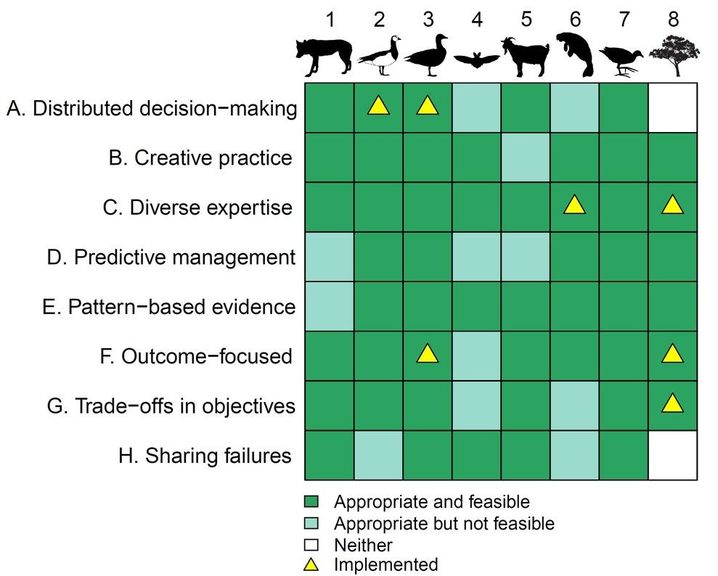

So far, so abstract. But in 2016, the first Interdisciplinary Conservation Network workshop was hosted by ICCS at the University of Oxford, in conjunction with STICS and CBCS at the University of Queensland. This workshop for early career researchers (the second incarnation of ICN is happening later in 2018) included wicked problem thinking for conservation conflict as one of three topics discussed at the event. Eight researchers, each with knowledge of a specific conservation conflict, were joined by mentors to discuss how the conventional and wicked processes were being implemented in the real world. And if they weren’t currently being used, are wicked thinking approaches even appropriate or feasible for these conservation conflicts?

Our output from the workshop has now been published in Conservation Letters.

We found that for each conflict case study, wicked problem thinking was not applied even though over three-quarters were deemed both appropriate and feasible. For half of the case studies not one wicked approach had been tried.

Having used our case studies to assess the current state of play as regards wicked problem thinking for conservation conflict management, we moved onto thinking how could we fill out those wicked approaches a little more. We came up with five emerging themes worthy of further study.

1. Distributed decision-making

Wicked problem thinking aims to achieve a greater devolution of decision-making to suit the uniqueness and dynamism of different conflicts. This may not always be straight-forward if governance structures or existing policy will not allow transfer of powers.

2. Diverse opinions

Embracing diverse voices can form an important route to foster creativity. Research into the links between knowledge co-production, creativity and conflict are required to fully understand the potential value of diverse voices.

3. Pattern-based predictions

Recognising patterns in ecological dynamics, human behaviour and links between the two can reveal processes acting as conflict triggers, such as the alienation of certain groups. Pattern-recognition analyses can make use of widely available sources of data.

4. Trade-off based objectives

Objectives guided by trade-offs between the interests of different stakeholders are likely to produce fairer outcomes than those based on a single group’s interests.

5. Reporting of failures

No case-studies shared failures transparently even though failures are inevitable, due to the complexities of socio-ecological systems. Communicating these openly can optimise management. It may be possible to encourage open communication by requiring different parties to formally commit to sharing risk and viewing failures as transient features of a wicked problem. While it is tough to develop ‘safe-fail’ cultures in conservation, honest discussions between managers and stakeholders about failures – and the potential to learn from them – provide an important step forward.

A thread which runs through all five themes is one of admission of complexity. Conservation scientists cannot solve these problems with conventional methods and to tame them we must share power with and get help from others whilst admitting that we don’t always have the solutions and will sometimes fall short. Wicked problems are a nightmare to manage, but by thinking and working holistically, we can be optimistic about their taming.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed