Despite the interest in species interactions, competition has seen less focus in this regard. An exception is Tom's work on competition between domestic and wild ungulates in the alps, in which he showed that Alpine chamois retreat to higher altitudes in the face of both high temperatures and grazing sheep - but that the effect of the presence of competitors is far more pronounced than the predicted effect of climate change. Thus, managing competition might be one way to mitigate for the consequences of climate change.

Last year, Francesco Ferretti visited the CEG from the University of Siena, Italy, on a Senior Fellowship sponsored by the Institute of Advanced Studies. One purpose of his visit was to work on analysing data on climate change and interactions between Apennine chamois (Fig. 1, above) and red deer. Red deer are currently expanding into the Apennines, where they compete with Apennine chamois (a subspecies of Pyrenean chamois recognised to be vulnerable to extinction). Francesco wanted to know if the impact of climate change would exacerbate the effect of competition (because the reduction in resources owing to climate change might make competition more intense), ameliorate the impact of competition (perhaps by leading to greater niche divergence between the species), or if the two would act independently. He brought with him data on foraging behaviour of chamois in an area that red deer have already expanded into, as well as data from an area that red deer have yet to reach. The results of his analyses have recently been published in the journal Current Zoology.

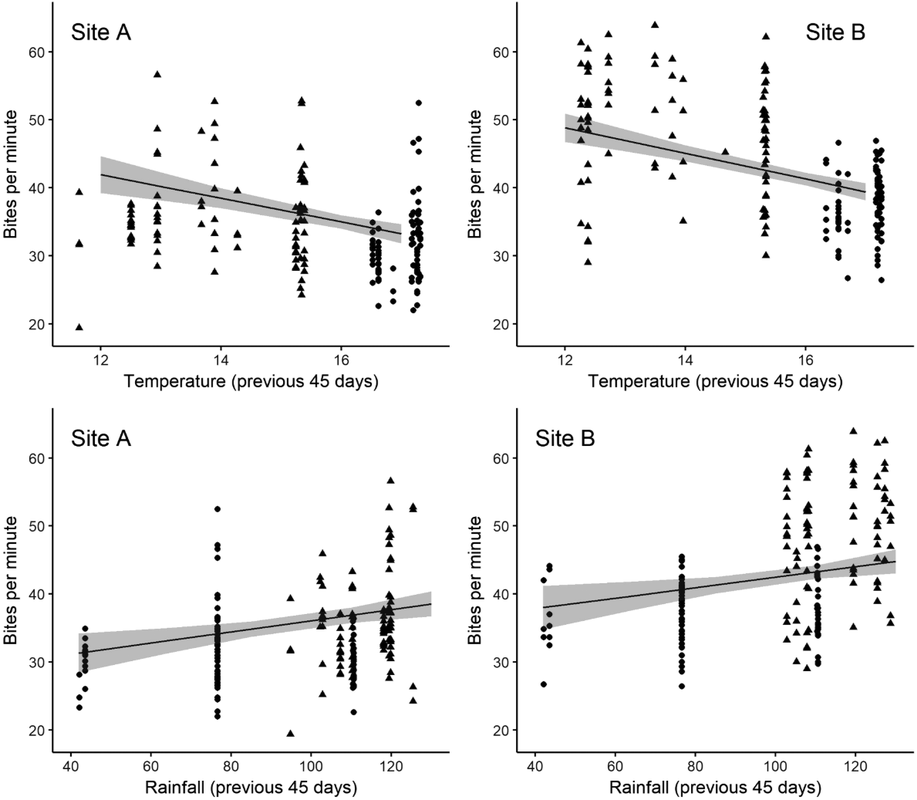

Francesco showed that climatic factors (temperature and rainfall) exerted a strong effect on chamois feeding behaviour. However, the presence or absence of red deer also impacted on the bite rate of chamois (a good indicator of the rate at which they take in food):

Importantly, in the context of Francesco's original question, there was no evidence of an interaction between the weather conditions and the presence of red deer. Thus, the two challenges appear to operate independently.

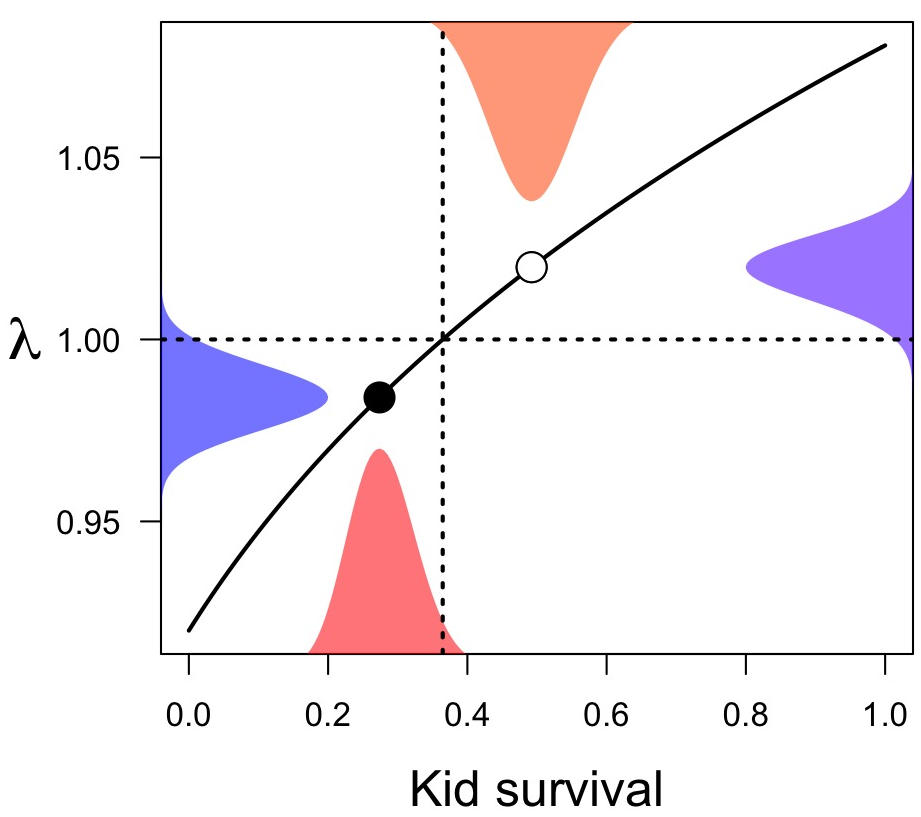

Francesco also showed that kid survival (indexed by the ratio of females to kids versus the ratio of females to yearlings in the different sites) was lower in the site with red deer than in the site without. Based on what is known about adult survival, we estimated that populations would only be stable (population growth rate, λ = 1) when kid survival was approximately 36%. In fact, the best estimate for kid survival was 49% in the site with no red deer but 27% in the site with red deer. Even given the uncertainty in that survival rate, there is a 95% chance that the survival rate in the site with red deer is too low for the chamois population to be self-sustaining (see Fig. 3). In general, increasing frequencies of drought conditions are likely to imperil Apennine chamois and related species - but that threat will be more pronounced in the presence of competitors, such as red deer, which are increasingly numerous throughout Europe.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed